May, 2010

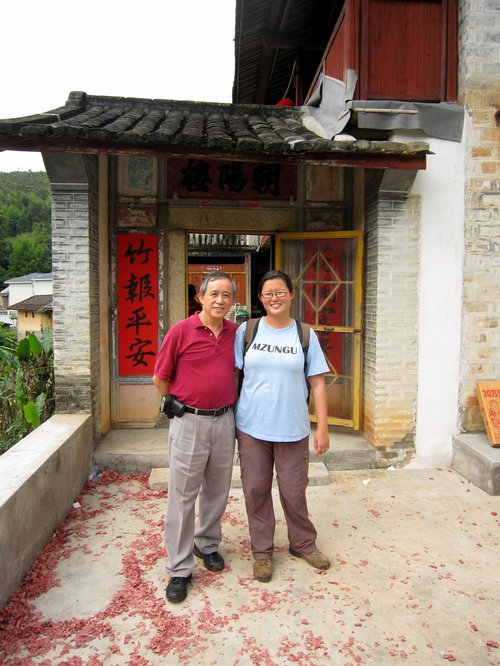

When you’re travelling and kitchenless, being invited to a homecooked meal is a very special thing. Especially when that meal is at one’s great grandfather’s house (above), which one is visiting for the first time.

The Soh ancestral home is nestled in the Hakka hillsides of Dabu, Guangdong Province, China. On our drive in from the urbanised lowland side of town, the main crops I spied were rice, vegetables, bananas, and fields upon fields of tobacco.

A view of the neighbourhood from the house:

The size and the relative elevation of Great Grandfather’s house suggest that he was fairly well-off in his day. I grew up with part-told, part-whispered, part-hinted, remainder-imagined stories about how he made his fortune opium-dealing in big bad Shanghai, but lost then lost it through an embezzling business partner and the toxic gambling habit of some secondary wife (not my biological great grandmother, Ah Pak assures me). Hence the need for my grandfather and later his nephew Ah Pak to board a slow boat to Singapore to eke out their own living, and hopefully make a fortune which they could send back to China.

Granddad never did catch his lucky break in Singapore. Regardless, he sent back to China what he could, even if it was sometimes just tins of rendered lard, recalls my Dad.

But then “lucky” is relative. When my Dad and his older sister Tai Gu (Big Auntie) first visited Dabu some 3 years ago, and mentioned the tough times their father went through in Singapore, Ah Pak’s sister who stayed back in China apparently replied, “Your father was the lucky one. He managed to get out.”

Having read Wild Swans by Jung Chang — a memoir of the travails of a politically well-placed family under Communist rule — I might be inclined to agree.

But now as I gaze at the bounty on the lunch table, I can only feel thankful that we’re here at all, that life has improved by this much within 3 generations. The rest of the elders can debate about who was lucky and who wasn’t. I am well aware that I am.

Most of today’s lunch is being whipped up by my cousin Zhiguang’s sprightly mother-in-law. I have no idea how old she is, given her long jet black hair, but she whirrs around washing and chopping vegetables and intestines alike at the pace of a ninja on speed.

I offer to help out but guests chipping in with muscle doesn’t go with the etiquette around here (more likely they’re worried I’ll just get underfoot I reckon). So I wander off to see the rest of the compound.

Here’s the wood fired kitchen. Not quite your designer magazine centrefold, possibly, but I think it’s gorgeously rustic.

Here’s one of 3 upstairs bedrooms, now long uninhabited and very dusty. Pak Meh tells me this was her room when she used to come visit with Ah Pak, a few decades ago.

Possibly the most fascinating spot in the house: A wall of photos by the upstairs stair landing. On the left are various relatives I’ve never heard of or met; on the right is Pak Meh, Ah Pak and their 5 kids. We estimated this photo to be around 35 years old.

And there he is. Great Granddad. I recognise the eyes, and the wide-as-a-movie-screen forehead both my Dad and I have.

I have so many questions for him. What were his Shanghai cowboy days like? How did he react to the advent of the Kuomintang and then the Communists? What did he like to eat? What would he think of China today? Could he have imagined it, or would he actually think — technological advancements aside — “same same but different?”

I wander back downstairs and outside, to the half of the house that hasn’t been maintained. Was this caused by dilapidation or destruction? Either way, it’s fodder for a helluva restoration project someday. *Wistful sigh*

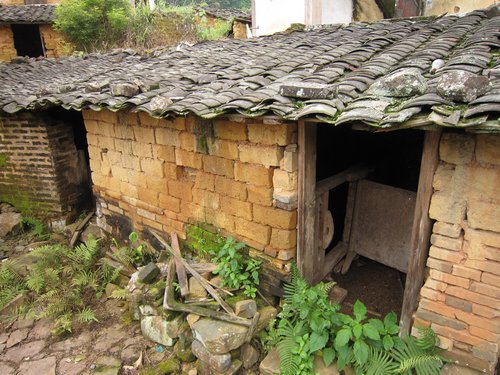

Outside, I stroll past a structure that used to house pigs, chickens and ducks…

… a room that looks like it was usually used for brickmaking. Further on, a closed-off courtyard labelled as a “gathering place for the Sohs”. Through the crack in the door I spy chickens scratching around in the grass. Must’ve been pretty lively around here back in the day.

A chain of hollers filter through the compound to announce that it’s time for lunch. We sit down to a feast of (from top left, clockwise) crunchy sliced ears, suan pan zhi (yam gnocci), salt-baked chicken with chunks of gizzard, a reddish-brown crystalline chewy dough I still can’t name, sauteed bamboo shoot slices, savoury glutinous rice, braised duck and yong tau foo (tofu stuffed with marinated minced pork and shitake mushrooms).

Yeah. I realise. Hakka food is very… brown. Not that you’ll keep thinking about it the minute you start chomping down.

The chicken and duck have an almost gamey flavour and muscle tone that makes me optimistic that the animals weren’t kept in battery cages all day. The bamboo has that lovely clean taste that suggests it was recently picked, and the suan pan zhi has bite but isn’t overly chewy, which suggests a generous yam-to-tapioca flour ratio. This be the real deal.

Oh wait, you didn’t think that’d be all, did you? How about some boiled intestines and their flappy bits stir-fried with ginger and salted vegetables? Not my favourite thing, but bang-on authentic, judging by how the elders are slurping it up.

It’s customary (or so we keep being told) for the hosts of a meal to toast elders and guests at these big meals. There is a laaaaaawtta maotai (the local firewater) and brandy swishing around the 2 tables. Especially ours, as Ah Pak is essentially the current patriarch of the clan.

Many many MANY gan-beis later, the table finally disperses. The women adjourn to pack leftovers away; the men adjourn for more drinks, smokes and nuts.

Ah Pak (far right) shoots the breeze with his China relatives. I lean over and whisper to Dad, “Who are those 2 old women who just showed up?”

Dad whispers back, “They live in the village, so we’re related somehow. But I have no idea how.”

They look fabulous when they laugh. The woman on the right kinda looks like my late paternal grandmother.

All too soon, it’s time to head back to town, but not before Dad and I get a shot together at the front door. See that red sign behind us? It just about reads: “Peace out”… from the Wu Tang Clan.